For a number of years, we have been studying the long-term stability of our tests. In 2013, Dr. David Schroeder carried out a study on Pitch Discrimination and Rhythm Memory and reported his findings in Statistical Bulletin 2013-12, Long-Term Stability for Pitch Discrimination and Rhythm Memory.

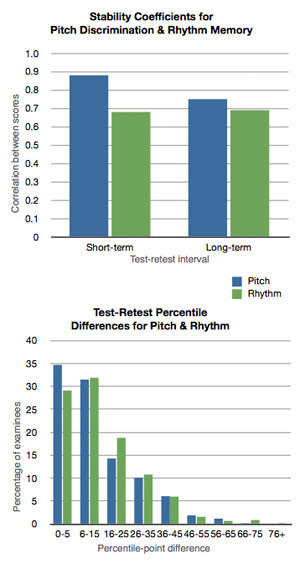

The short-term and long-term correlations for the Pitch and Rhythm tests are shown in the first accompanying figure. In the second figure, the distributions of differences in percentile scores for the two testings are shown for the long-term samples. As shown in the figure, most of the examinees show relatively small percentile differences between testings, with Rhythm Memory showing somewhat larger differences than Pitch Discrimination, apparently due to the greater short-term variation on the Rhythm test.

For Pitch Discrimination, we arranged for 426 examinees to retake the test at an interval of 1 to 22 years from their original testing (the “long-term sample”). In addition, 65 examinees retook Pitch Discrimination less than one year after their original testing (the “short-term sample”). For both samples, examinees showed a small practice effect, with scores on the retest about one-and-a-half to two points higher (on an 80-item test) than on the original testing. In terms of rank-ordering, examinees’ scores on the retest correlated .75 with scores on the original testing for the long-term sample and .88 for the short-term sample. Thus, Pitch Discrimination shows relatively high stability over long periods of time, and a portion of the change in scores appears to be due to short-term fluctuations (reflected in the short-term correlation) rather than long-term change.

When we divided the long-term sample for the Pitch test into those who were 14 to 19 years old at their original testing and those who were 20 and up, the correlation was higher for the older examinees (.81) than for the younger examinees (.66). Thus, the stability appears to be higher for examinees who were tested after their teen years.

For Rhythm Memory, the long-term sample consisted of 436 examinees tested 1 to 24 years after their original testing, and the short-term sample consisted of 122 examinees tested less than one year after their original testing. Both samples showed essentially no practice effect between their two testings. In terms of correlations, scores on the retest correlated .69 with scores on the original testing for the long-term sample and .68 for the short-term sample. Although the short-term correlation is a little lower than we would like to see (and may have been influenced by sampling error), it is gratifying that for the long-term sample, the longer time period between testings does not appear to have caused any material decline in the stability of scores.

When one divides the long-term sample by age at original testing, the correlation is .67 for ages 14-19 and .71 for 20 and up, and so there is not much of a difference there.

In general, these findings support our contention that aptitudes are stable over long periods of time.